He isn't in Serbia, he's living with grandpappy in Florida LMAOMore proof Null in Serbia is fake and gay or he is terminally online to ridiculous basement dweller levels. Either way it is not a good look.

Podcast Flyer

Welcome Statement🧅

Welcome to Onionfarms. All races, ethnicities, religions. Gay, straight, bisexual. CIS or trans. It makes no difference to us. If you can rock with us, you are one of us. We are here for you and always will be.

Follow Onionfarms/Kenneth Erwin Engelhardt

Onionfarms Merchandise(Stripe Verified): Onionmart

Onionfarms.net (Our social network site powered by Humhub).Register and up your own little space to chat and hang out in.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Joshua Conner Moon - Kiwi Farms Joshua Moon Megathread

- Thread starter Randy Know

- Start date

- Featured

-

- Tags

- 1776hosting 1776hosting.com 2tsuki bear chemical cringe deceptive deviant dick fancy fancy bear farms fat flow flow chemical fraud huckster josh joshua conner moon joshua connor moon joshua moon kengle kenneth erwin engelhardt kiwi kiwifarms mental illness moon null onionfarms picture pizza stocking vincent vincent zhen warwick ri zhen

Joshua Moon the owner of Kiwifarms

Username: null

Iq: null

Penis size: null

Personality: null

Skills: null

Iq: null

Penis size: null

Personality: null

Skills: null

Remember, Null gets to have Schadenfreude over all of his former friends when they have something bad happen to them, but if they do it in return when something bad happens to Null, they are malignant narcissists trying to turn Null gay.

The amount of "gay groomer" fantasizing when it comes to Null and Rekieta amongst these trad-LARPing Kiwis in the comments under Elissa's clips is so revealing. They're in the comments fantasizing about Rekieta being this older gay man who is trying to introduce a younger Null to the homosexual degenerate underworld ("Just wear the Baldo, Josh, everything will be forgiven", "Let's share a Balldo together, buddy."). They have to make it sexual and suggest there is sexual grooming involved even when there is not. I have never heard or seen anything suggesting that Rekieta is sexually lusting after Null. This is entirely the deranged obsessed fantasy of KF. It's because people have never seen Null as an adult grown man - and Null has made sure they never see him in in his 30s, by using Rekieta as his trad-shield - that they have this infantilizing view of Null. Null has certainly gone out of his way to present himself as someone who was corrupted by online homosexuals into "thinking I was gay", and Kiwis are trying to fit Null's latest dispute with Rekieta into this mold ("So, the last two times you initiated conversation with jersh, you weren't wearing pants? Not. Ghey. Everyone!").

Literally this:

The reality is: Null has a history of deliberately cultivating public drama and public break ups with his former friends so he can exploit these public disputes for weeks and months on end as "exclusive drama scoops" on MATI. Null deliberately sexualizes his personal disputes with his former friends, even when there is no sexual innuendo involved or suggested, to make them seem deserving of his scorn for being gay or degenerate. Null uses sex to humiliate his former friends, while no one asks the question of why Null is doing this again and again (it's very obvious projection because he himself was sexually humiliated for his own kinks, but he will forever deny this). He's been following this same pattern ever since his dispute with Clara Stockings: Null will have a very public dispute with someone in front of an online community he's involved with (whether that's Blockland, 8chan or KF), Null will then sexually humiliate the other person to make them seem deserving of his scorn and rejection. On KF, Null has made sure to surround himself with the most out-there moral police fundamentalists who are very susceptible to such sexualized arguments. Every single public dispute that Null has ever had with someone, male or female, has followed this same pattern.

There are people in the comments fantasizing about who Null himself is, commending him for "standing by his principles"... how the fuck do y'all know that Null is "standing by his principles"? You literally know NOTHING about this guy. You don't know where he is, you don't know whom he's with, you don't know what he's doing whenever he's not on KF or doing MATI. You don't know if Null is actually living the life he professes to want to live on KF and MATI, so what the fuck are y'all running your mouths about? Rekieta probably knows more about Null than any of you people do - which I guess is why Rekieta warned Null about discovery in the Russel Greer lolsuit, and suggested it might reveal something embarrassing about Null. I obviously have no ideal what Rekieta is referring to, but all these people who have gone along with Null's trad-LARP might have to suffer an eventual suspension of disbelief.

The amount of "gay groomer" fantasizing when it comes to Null and Rekieta amongst these trad-LARPing Kiwis in the comments under Elissa's clips is so revealing. They're in the comments fantasizing about Rekieta being this older gay man who is trying to introduce a younger Null to the homosexual degenerate underworld ("Just wear the Baldo, Josh, everything will be forgiven", "Let's share a Balldo together, buddy."). They have to make it sexual and suggest there is sexual grooming involved even when there is not. I have never heard or seen anything suggesting that Rekieta is sexually lusting after Null. This is entirely the deranged obsessed fantasy of KF. It's because people have never seen Null as an adult grown man - and Null has made sure they never see him in in his 30s, by using Rekieta as his trad-shield - that they have this infantilizing view of Null. Null has certainly gone out of his way to present himself as someone who was corrupted by online homosexuals into "thinking I was gay", and Kiwis are trying to fit Null's latest dispute with Rekieta into this mold ("So, the last two times you initiated conversation with jersh, you weren't wearing pants? Not. Ghey. Everyone!").

Literally this:

They always talk about assholes and dicks and, you know, obviously they're very masculine and homophobic, and all their fantasies revolve around other men, their dicks and asses. Cool.

The reality is: Null has a history of deliberately cultivating public drama and public break ups with his former friends so he can exploit these public disputes for weeks and months on end as "exclusive drama scoops" on MATI. Null deliberately sexualizes his personal disputes with his former friends, even when there is no sexual innuendo involved or suggested, to make them seem deserving of his scorn for being gay or degenerate. Null uses sex to humiliate his former friends, while no one asks the question of why Null is doing this again and again (it's very obvious projection because he himself was sexually humiliated for his own kinks, but he will forever deny this). He's been following this same pattern ever since his dispute with Clara Stockings: Null will have a very public dispute with someone in front of an online community he's involved with (whether that's Blockland, 8chan or KF), Null will then sexually humiliate the other person to make them seem deserving of his scorn and rejection. On KF, Null has made sure to surround himself with the most out-there moral police fundamentalists who are very susceptible to such sexualized arguments. Every single public dispute that Null has ever had with someone, male or female, has followed this same pattern.

There are people in the comments fantasizing about who Null himself is, commending him for "standing by his principles"... how the fuck do y'all know that Null is "standing by his principles"? You literally know NOTHING about this guy. You don't know where he is, you don't know whom he's with, you don't know what he's doing whenever he's not on KF or doing MATI. You don't know if Null is actually living the life he professes to want to live on KF and MATI, so what the fuck are y'all running your mouths about? Rekieta probably knows more about Null than any of you people do - which I guess is why Rekieta warned Null about discovery in the Russel Greer lolsuit, and suggested it might reveal something embarrassing about Null. I obviously have no ideal what Rekieta is referring to, but all these people who have gone along with Null's trad-LARP might have to suffer an eventual suspension of disbelief.

SekturGeist

Registered Member

I wonder what deranged things he posts in his matrix chat.

Chrysler Building

Hellovan Onion

Remember, Null gets to have Schadenfreude over all of his former friends when they have something bad happen to them, but if they do it in return when something bad happens to Null, they are malignant narcissists trying to turn Null gay.

The amount of "gay groomer" fantasizing when it comes to Null and Rekieta amongst these trad-LARPing Kiwis in the comments under Elissa's clips is so revealing. They're in the comments fantasizing about Rekieta being this older gay man who is trying to introduce a younger Null to the homosexual degenerate underworld ("Just wear the Baldo, Josh, everything will be forgiven", "Let's share a Balldo together, buddy."). They have to make it sexual and suggest there is sexual grooming involved even when there is not. I have never heard or seen anything suggesting that Rekieta is sexually lusting after Null. This is entirely the deranged obsessed fantasy of KF. It's because people have never seen Null as an adult grown man - and Null has made sure they never see him in in his 30s, by using Rekieta as his trad-shield - that they have this infantilizing view of Null. Null has certainly gone out of his way to present himself as someone who was corrupted by online homosexuals into "thinking I was gay", and Kiwis are trying to fit Null's latest dispute with Rekieta into this mold ("So, the last two times you initiated conversation with jersh, you weren't wearing pants? Not. Ghey. Everyone!").

Bit of a chicken and egg thing because the power users on KF do this too. Did Josh train them to do it or did they train him? When I first got there it disturbed me to see how often Kwiffar posted disturbing and explicit rape fantasies. Some of this was just "suck the girldick" but they've written a lot of pornographic fantasies about how they think they'll be raped by trannies. What's interesting is how its almost exclusively the male users who do this; female autists on KF don't post about "girldick."

When I looked at the abortion sperging thread HHH was still posting in it and every single post was a rape fantasy about a teen girl getting raped and needing an abortion; he used that to plead the pro-abortion case. It was very similar to how other Kwiffar act with extremely detailed fantasies about scenarios, sexual positions, number of attackers, etc. and while he left the thread eventually it really became clear to the end that he was getting sexual gratification about writing rape fantasy fanfic.

What makes HHH different from other Farmers is that his rape fantasies were explicitly heterosexual whereas other Farmers project themselves into the role of the victim, being raped by another male. It really is a circlejerk for these people, when threads devolve into tranny sperging they will start exchanging rape fantasies with each other, its very grotesque. They claim to hate trannies but they also want to have risky and dangerous sex with them.

Josh has a similar attitude like those Blockland posts where he fantasized about raping his mom (I think?) or raping the girl who rejected him. Though at least he has the guts to project himself into the active role of the rapist, other Kwiffar are born buttsluts.

The obsession with homosexuality and fantasies about participating in homosexual acts is all over the Farms. Its clearly linked to a sexual desire to be humiliated but tbh I can't really make heads or tails of it. Josh and the Kwiffar are clearly excited by the possibility of contact with gay men and transvestites. Weirdly enough its HHH that seems to be the most heterosexual user left on the Farms.

KampungBoy

Local Moderator

That's the grossest thing about the farms, yes. They hide their freaky fetishes behind pretending to care about people.

Kiwifarmers making fun of lolcows is like the pot the kettle black.

TheAnimeRetard

Registered Member

The userbase of KF is pretty large. It honestly depends who you're talking about.Kiwifarmers making fun of lolcows is like the pot the kettle black.

If it is the loudest most autistically terminally online user then definitely.

If I was one of this guy's 5 kids I would hope and pray for his death every single day of my life.Rekieta to Null: "You're a lovable retard. I like you. You don't believe me but I always have."... what's the point of telling Null this over and over, telling him how much brotherly love you have for him? Love only those worthy and welcoming of your love, fuck all the rest. Null is a hater, he only understands hate so don't waste your love on him, give him what he actually wants, which is your hatred, not your love.

Rekieta, I don't know if you will ever see this, but seriously: Null is not gonna bury the hatchet and just talk shit over. Once he burns a bridge, it's burned forever. This drama between you is just way too profitable for him over "gay shit like friendships". You are the Youtuber with the bigger channel and the millions of views, so by milking the drama between you, Null is making money off of your audience. You really don't seem to understand how Null looks at his drama purely as a business opportunity to bring disappointed ex-Rekieta viewers over to KF and MATI. That's the bottom line, and the quicker you figure that out about him, the easier it will be to completely ignore him going forward.

Rekieta: "Hey faggot, message me so we can work this out.", that's never gonna happen. Null can definitely "afford this gay bullshit" if that Mother Jones claim about the $300k in bitcoin was true.

We must all aspire to reach this blissful state of Pure Zen:

View attachment 40869

Dindu Nuffin

Nigress/Nigresses LGBTIAQ2SP+ BLM Ukraine Palestine Defund The Police BBW

Remarkable Onion

With "friends" like that, who needs enemies?That's the grossest thing about the farms, yes. They hide their freaky fetishes behind pretending to care about people.

AshleyBloatedSwalloHole

The Official Coward of Onionfarms; Cannot Talk To A Fat Woman

An Onion Among Onions

To anyone who doesn't know, this is Ashley Hutsell Jankowski. A woman who has multiple times tried to destroy this very website that she loves posting in.If I was one of this guy's 5 kids I would hope and pray for his death every single day of my life.

I don't want associations with kiwifarms or any offshoot, both because I find the culture morally deplorable and because I have a storied history with stalkers from the alt-right. I would be far less abrasive if you weren't being a weird dickhead about this.

You have three days to delete this thread and get these three demonic losers out of my personal life or I'm filing a complaint with the medical board of your state.

AshleyBloatedSwalloHole

The Official Coward of Onionfarms; Cannot Talk To A Fat Woman

An Onion Among Onions

In fact, she got this website off Hostgator.

Not with shrinkflation fatboy.

Not enough minerals Not enough

minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals

Hellovan Onion

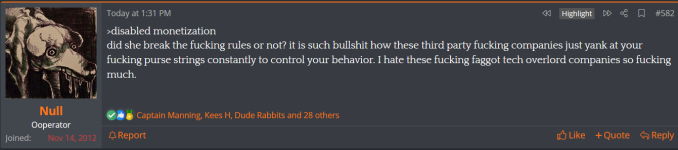

Null talks about his micropenis.

Not enough minerals Not enough

minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals

Hellovan Onion

View attachment 40773

I am surprised you guys are not aware that Null is the most moral person on the face of the earth. Here he is morally calling for the doxing of a baby still in the womb.

>moralfaggingPretty based, ngl.

ipreferpickles

An Onion Among Onions

AshleyBloatedSwalloHole

The Official Coward of Onionfarms; Cannot Talk To A Fat Woman

An Onion Among Onions

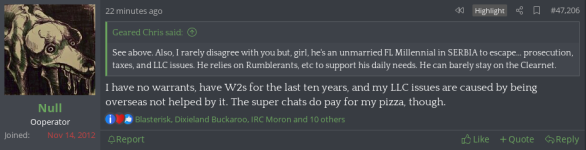

Maybe Sssniperwolf should get a real job, like if Youtube is your main avenue of making money, you're kinda asking to get your shit kicked in.View attachment 40922

Null thinks Sssniperwolf getting demonetized is oppressive.

Not enough minerals Not enough

minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals

Hellovan Onion

Josh Moon is coming for the Schutzstaffelsniperwolf Hate Thread next, watch out !

Benevolent Leader, Kim Josh Il.

Not enough minerals Not enough

minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals Not enough minerals

Hellovan Onion

Now I want to see a "The Easy to Track File Hall of Fame" thread with an equally lolcowish OP as the username one.Benevolent Leader, Kim Josh Il.

View attachment 40924